Purchase this book

(click here to change currency)

Once Joseph Stalin took the lead of the Soviet Bolshevists after the death of Vladimir Lenin, he quickly turned away from Lenin’s New Economic Policy, with its many concessions to capitalism, to a policy of one-country socialism, driven by his first Five Year Plan (1928) and a plan that other Bolsheviks like Lenin and Trotsky thought impossible. That shift, radical, forced Stalin to “urbanize” the USSR’s vast rural areas—that is, to impose a factory-like model on the Soviet countryside to maximize its efficiency. That required collectivizing the numerous Soviet farms—making large farms of the numerous small farms. Ukraine was to be the model republic due to its vastness and black, fertile lands. Not only were the republics to be collectivized, they were also to be Russified for the sake of model efficiency and centralization of control. And so, while Stalin, early in his political life, preached respect for the cultural diversity of its many republics and the right of secession of any republic, the need to collectivize the Soviet farms for the sake of one-country socialism demanded compliance.

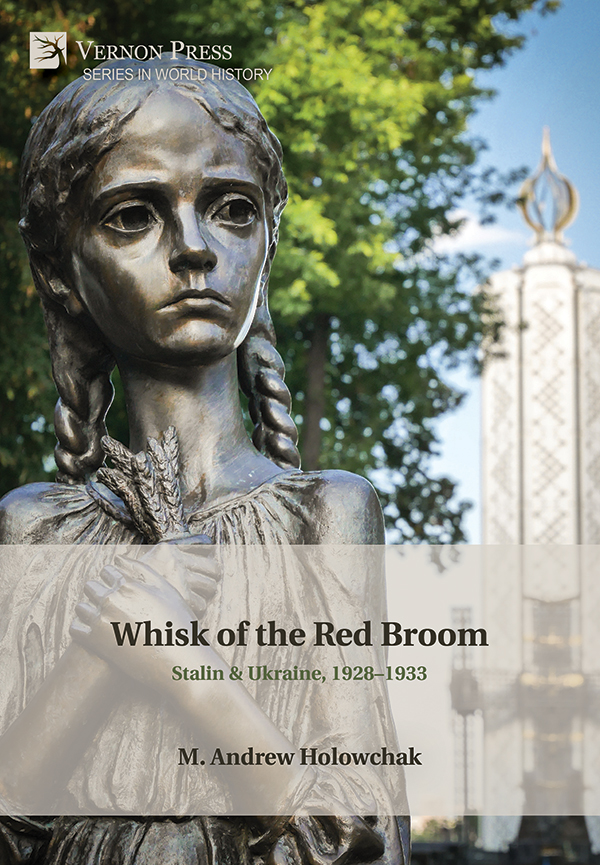

Ukrainian peasant-farmers were non-compliant, for they readily saw that the State was asking them for everything and giving back nothing but the pledge of efficient farms to benefit the State, and non-compliance forced Stalin’s authoritarian hand. He imposed laws that brutally punished non-compliant peasants, called “kulaks.” The plan was dekulakization. The intransigents were dispossessed of their property, alienated from other villagers, exiled, and exterminated. The result in Ukraine was the gross inefficiency of both collective and individual farms. That led to intolerance of Ukrainian culture and theft of Ukrainian grain, and even all other findable foodstuffs, to punish Ukrainians. The end was a great famine in 1932 and 1933 in which some four million Ukrainians died.

Did Stalin believe that he could urbanize the Soviet countryside? Did Stalin think that socialism could take root in the backwater Soviet Union without the aid of Western succor? Did Stalin hate Ukrainians because many pressed for a cultural identity separate from that of Russia? Had Stalin’s plan of dekulakization from the beginning been a policy of political genocide? Those are some of the many questions I aim to answer in this book. I focus much on Stalin’s writings in the efforts to ascertain his mindset as a dictator.

List of Figures

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1 Man of Steel

Chapter 2 The Death of Lenin

Chapter 3 Stalinism & Ukraine

Chapter 4 Collectivizing Ukrainian Farms

Chapter 5 Compulsatory Collectivization

Chapter 6 The “Need” of Dekulakization

Chapter 7 The Process of Dekulakization

Chapter 8 Ukrainians’ Resistance to Dekurkalization

Chapter 9 Respite & Resumption

Chapter 10 The Problem of Nationalization

Chapter 11 The Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933

Chapter 12 Holodomor, Causes & Consequences

Chapter 13 Stony Soviet Silence

Chapter 14 Stalin’s Marxist Utopia

Afterword

Figure Credits

Index

M. Andrew Holowchak, Ph.D., is a professor of philosophy and history. He is the author/editor of over 67 published books and some 350 published essays on topics such as ethics, ancient philosophy, science, psychoanalysis, Ukraine, and critical thinking. His current research is chiefly on Thomas Jefferson—he is acknowledged by several scholars to be the world’s foremost authority on the thinking of Jefferson—and has published 28 books and over 225 essays, formal and informal, on Jefferson. He has a passion for gardening and enjoys lifting weights (former Michigan superheavyweight powerlifting champion), bike riding, conferencing, and talking about Thomas Jefferson and historiography.

Russian Revolution, Ukraine, Bolshevism, Nationalism, Holodomor (the Great Famine of 1932-1933)

See also

Bibliographic Information

Book Title

Whisk of the Red Broom: Stalin & Ukraine, 1928-1933

ISBN

978-1-64889-860-0

Edition

1st

Number of pages

262

Physical size

236mm x 160mm